Califuerte

I lost and old friend this week. We hadn’t been very close for quite a while—the last time I even spoke to him was a few years ago now. He was a pretty important person in my life for a good decade or so, though. Since funerals and celebrations of life aren’t really an option during a pandemic, I sort of feel the need to say a few nice things about a guy who frustrated, hurt, and offended, but also loved a lot of people. And a lot of people loved him back. To me, he was a compassionate and genuine friend.

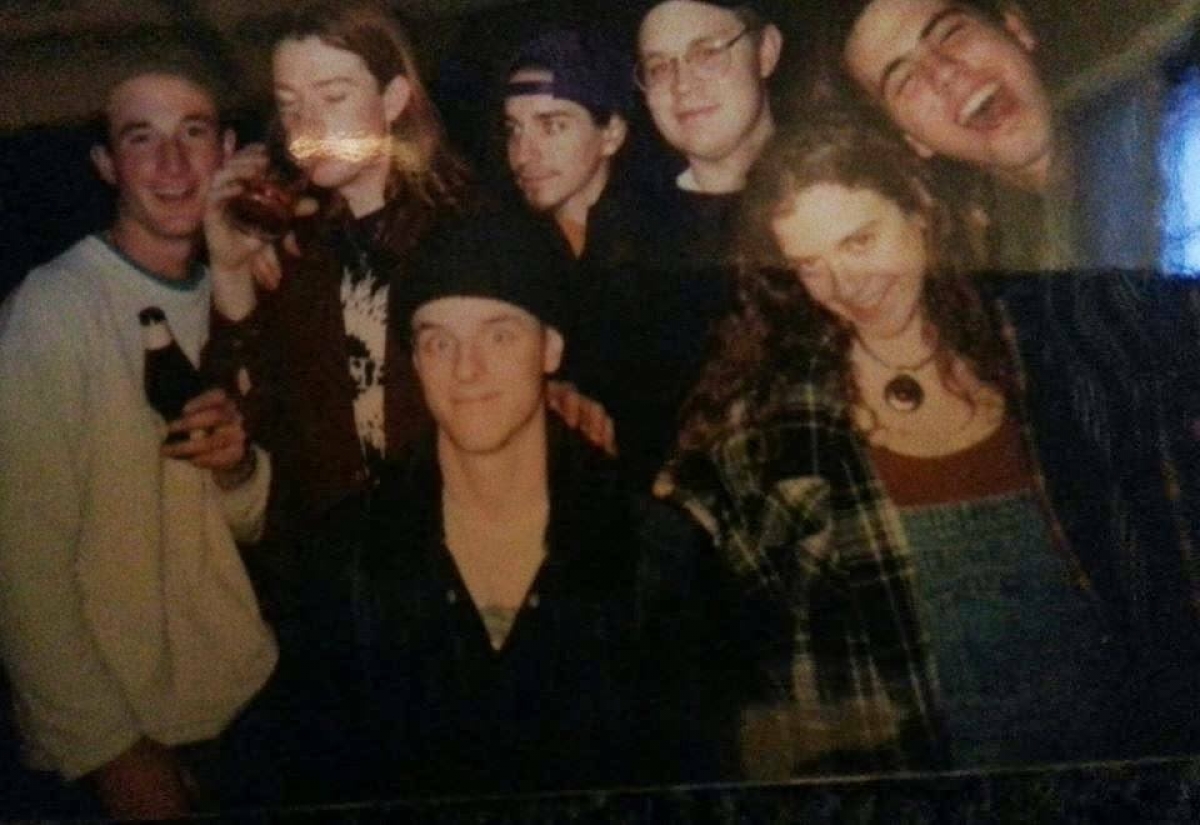

I first met Rodney in 7th grade. He was a punk rock, skater kid who hung with a diverse crowd—many of them outside of my comfort zone. We did have lots in common as far as music and art went, but never really hung out much outside of school. He had a rough life as a kid. He left home at a pretty young age, and didn’t always have a great place to sleep. We were friendly through highschool, though. Well, as much highschool as he made it through.

Sometime in the early 1990s, we ended up working for Valley Records together, and he asked me to try out for his band, Floss. They had a basement studio under a house in rural Woodland. I was told the owner had a bit of a meth problem, but he was a big fan of the music. He had built a pretty nice practice pad—complete with drum riser, shelves for amps and drinks, and lots of fly strips on the cieling that Jon (Wilson, our late guitarist) would continually get his hair caught in. That audition was the most awkward I have experienced to date.

I had reacently left college and didn’t have a big enough amp to use at the time. Rodney said they had an amp in the basement I could use. What he didn’t say was that he hadn’t told Joe, the current bass player, that he was no longer in the band. Joe hadn’t shown up for practice in a few weeks or maybe a month, but he did show up that night. He was understandably upset, and aggressively packed up his amp and stomped out.

Don’t worry. Joe and I worked it out, and even ended up writing and recording a few songs together years later. Anyway, I got the gig, and that’s where I really got to know Rodney.

The band made enough money to keep a private rehearsal space, but not enough to buy a van, so we frequently took two cars to gigs. Rodney and I spent a lot of time on the road together. There were lots of passionate discussions about the Flaming Lips, death metal, and music in general. There was also plenty of shit talking about people we knew, people we didn’t know, and our general dissatisfaction with society as a whole.

Durring these conversations, Rodney would be warming up. In mid sentence, he would suddenly clear his throat, and belt out a blues run, melody, or just scream. Sometimes he would sing the rest of the sentence, sometimes he would just sing notes, then finish his thought. It was very bizarre, but strangely comforting.

One night on the way to a gig in Sacramento, he put a dubbed copy of the new Grant Lee Buffalo album, Mighty Joe Moon, in my tape deck. We were on I-5 just outside of Woodland, and there was a thunderstorm to the north—kind of a rare sight for Yolo County. We watched the storm crawl along with us while Lone Star Song, Mockingbirds, and It’s the Life played. I don’t think either of us said a word until we got into the city. I still think about that drive during thunderstorms.

I was a pretty sheltered kid and young adult. Playing in Floss exposed me to a lot of things I wasn’t the most comfortable with, but Rodney always took this into account. He exposed me to the beautiful, chaotic underbelly of society (at least that was how it appeared from my sheltered perspective), all the while being a calm, reassuring presence. He really had my back, and I totally trusted him. He never gave me a reason not to.

We played pretty regularly on Haight Street, and usually wouldn’t get packed up until about 3 a.m. After one of these gigs, we went to get my car to pull it up front to load out, and found it wasn’t there. We weren’t sure if it was stolen or towed, so we walked down the street to a police station where we found out it had been towed. Rodney hailed a cab, rode with me down to the impound yard, helped me cover the bill and cab fare, and we drove back to the gig where Jon was waiting for us on the curb with our gear.

Rodney really cared about me. I know because he told me that he did. Regularly. I’m paraphrasing here…

“Mark, I would feel like the biggest piece of shit if you ever got mad at me. You are such a good person, I’m not going to let any of those fuckers corrupt you.”

“No. Dude, I’m serious.”

And he was.

It feels like a wasted gesture to share these memories with the empty internet—and with anyone but Rodney, for that matter. I know he had much closer relationships with many other people, and pretty bad relationships with others. To me, though, he was nothing but kind, understanding and protective. Being in that band with him during my early adulthood played a big part in who I am today. I am really grateful to have known him. My heart goes out to everyone else who is, too.